Introduction

It has long been recognized that environmental science education can play a central role in raising public awareness of anthropogenic impacts on natural systems (e.g. Diduck 1999). Many studies have assessed the impact of introductory environmental science courses on the values and attitudes of K-12 and undergraduate students about environmental issues (Leeming et al. 1993; Rickinson 2001). The general consensus is that such courses tend to have positive impacts on environmental attitudes, including heightened awareness of environmental issues and greater commitment to mitigating their own impacts as revealed through their actions (Carpenter 1981; Benton 1993; see Leeming et al. 1993, Zelezny 1999, or Rickinson 2001 for meta-analytic reviews).

Student-active approaches in teaching undergraduate science (as defined in McNeal & D'Avanzo 1997) have been demonstrated to have greater impact on student learning over classic, lecture-based approaches (National Research Council 1999, 2000). In this study our first goal was to examine whether active teaching approaches likewise effectively influence student attitudes concerning environmental issues. Although other studies have assessed changes in values, we are not aware of any to date that have attempted to assess the impact of student-active approaches on environmental values.

Our second goal in this study was to develop a survey that effectively assessed college students' environmental values and that linked specific information taught with changes in students' views between pre- and post- surveys. Many survey instruments exist for assessing environmental attitudes, particularly when applied in a pre- and post-intervention protocol (Leeming et al. 1993; Zelezny 1999; Rickinson 2001). However, few are specifically designed for undergraduate students in the sciences and most are not constructed to explicitly account for the connection between learning ecological principles and changing environmental attitudes. Few surveys attempt to query ecological learning and understanding directly or indirectly while simultaneously assessing environmental attitudes. A survey instrument that connects environmental issues with course content, and consequently the student-active teaching approaches used to deliver that content, would be most useful for assessing the impact of these teaching methods on student attitudes.

Therefore, we developed a survey designed to assess student perceptions of environmental issues as well as their knowledge of the ecological principles underlying those issues. In this paper, we discuss the validity of this survey and how using it has influenced our teaching of environmental science courses. For initial assessment, the novel instrument was coupled with an established instrument to determine if attitude changes were consistent between both surveys. We view this survey as a first step towards further investigation about relationships between changes in student attitudes and the course content and its manner of presentation. We applied these surveys in a pre- and post-course assessment of undergraduate students at two different institutes. We decided to pursue similar studies at two very different educational institutions in order to broaden the demographics and increase sample size. The two educational institutions involved in this study were Phoenix College (PC) and Virginia Military Institute (VMI). VMI is a four-year public military college, and its students are mostly white (87%), mostly male (92%), and young (applicants must be between 16 and 22 years old). PC is a public, two-year, Hispanic-serving institution (30% Hispanic). The median age of its students is 25, and 60% of students are female. The instructors of the participating courses used similar student-active teaching approaches, including many of the materials published in Teaching Issues and Experiments in Ecology (TIEE). In addition, one of us (EOB) is an author of a TIEE Experiment (Ortiz-Barney et al. 2005).

Methods

We developed a survey for pre- and post-course distribution that coupled an established instrument for measuring environmental values with our own, novel survey querying student perspectives on specific environmental conflicts. The latter was developed for three reasons: 1) to assess specific dimensions of environmental values that are not explicitly measured in standard assessment instruments; 2) to provide a context for queries in which the complexity of environmental conflicts and underlying ecological dynamics are considered directly (rather than implicitly); and, 3) to assess student understanding of specific aspects of ecology underlying environmental issues. Therefore, our new survey addressed the two project goals described above.

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) survey

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) is an established survey instrument designed to gauge anthropocentrism (also termed egocentrism) or ecocentrism in environmental attitudes and values (Dunlap et al. 2000). With it we could address our first goal (assessing attitudinal change) but not our second goal (linking specific pedagogy with this change) in this study. The instrument includes a series of statements to which respondents state agreement or disagreement on a standard Likert scale. For example, the survey includes the statement:

Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs.

Participants then indicate if they would characterize their response to this statement as strongly agree,

agree,

neutral,

disagree,

or strongly disagree.

A response of strongly agree

indicates a high degree of anthropocentrism in an individual's perspectives on environmental concerns while a response of strongly disagree

indicates a high degree of ecocentrism. Statements are either positive or negative with respect to environmental values. The example above would be considered negative with respect to ecocentrism, and disagreement with the statement indicates a high degree of ecocentrism. Other statements, such as:

The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset.

are positive with respect to ecocentrism, and agreement indicates an ecocentric (or pro-environment

) perspective. Each ordinal response is scored on a scale of 1-5, with the highest value corresponding to the most ecocentric response. In the first example (a negatively ecocentric statement) a response of strongly disagree

would be scored a 5 and a response of strongly agree

would be scored as 1. The scale is reversed for positively ecocentric statements. The minimum total score of 15 indicates extreme anthropocentrism, while the maximum score of 75 indicates extreme ecocentrism.

As should be apparent from the representative examples, the NEP statements are decidedly simplistic. This is a necessary symptom of one of the NEP’s strengths, that is, its applicability and repeatability across a broad spectrum of age groups and social backgrounds. However, for students even moderately versed in the fundamentals of ecology or environmental science, the implications of these simplistic statements are too easily apparent. This raises a concern for applying the NEP as a pre- and post-course assessment for courses in these areas. Students may perceive an agenda on the part of the instructor, and therefore may not respond honestly. This might be due to conditioning after a semester of study in the course — student performance in classes can hinge on their ability to detect what an instructor 'wants to hear' — or it may be an impulse to please the instructor, even under the condition of anonymity. It is also possible that students might respond more negatively if they perceive an agenda within the survey (particularly if they harbor negative feelings toward the instructor).

The Environmental Conflict Overview (ECO) survey

We developed the Environmental Conflict Overview (ECO) survey as a companion to the NEP in our pre- and post-course student assessments. The ECO survey is comprised of brief descriptions of specific environmental issues, generally highlighting stakeholder conflicts. Each case overview is followed by a series of statements to which students respond on a Likert scale, similar to the NEP. The statements are generally designed to assess a specific aspect of student perspective on the conflict, rather than simply anthro- or ecocentrism. The conflicts themselves are selected to resonate with undergraduate students with a general understanding of ecology or environmental biology. They are also intentionally divisive. Our hope was that this would elicit more personal (and therefore honest or candid) reactions from the students, and potentially reveal sociological biases in perspectives. For example, the survey distributed to cadets at the Virginia Military Institute included a review of the environmental threats posed by a chemical weapons incineration facility operated by the United States on Johnson Atoll. Following each set of Likert-scale responses, students had the opportunity to discuss their opinion of the issue further in a free-response format.

Scoring the ECO survey responses is less straightforward than the NEP. Each statement is first characterized according to the aspect of environmental perspective that it is designed to reveal. The survey statements were designated as querying:

- Awareness of ecological principles fundamental to the conflict;

- The degree to which economic aspects are given priority in resolving the conflict;

- General anthropocentrism in student's assessment of the conflict;

- If parity among stakeholders is favored as a resolution;

-

If a student is particularly 'protective' of the environment. These statements were intended to reveal

knee-jerk

environmental conservatism in student perspectives.

The Likert-scale response was scored from 1-5 for each statement, with a higher score indicating greater prevalence of a particular trait in the respondent's perspective. For example, one section of the survey reviewed issues in management of invasive species. The following statement is then offered:

The cost of preventing species introductions — or removing invasive species — is too high to consider it.

Agreeing with this statement clearly reveals that the respondent places an emphasis on economic aspects of the issue. Therefore, a response of strongly agree

would score a value of 5 in the economic priority

category (likewise, strongly disagree

would score 1 in this category). The complete survey and annotated details of the scoring procedure are provided as supplementary materials for this article (see Resources).

Questions were scored in more than one category if they reflected more than one dimension of environmental perceptions. Strong disagreement with the example statement above could also be considered indicative of ecological conservatism; certainly, the cost of control or eradication must be considered in management of invasive species. Therefore, a response of strongly disagree

to this statement scored 5 in the category of ecological conservatism. Here it must be noted that this survey was designed to assess differences in pre- and post-course perspectives. The categorical scores provided a relative measure of a certain aspect of environmental perspectives, which were primarily relevant in pre- and post-course comparison. Free-response statements were not scored, but they were used to gain qualitative insight into the perspectives of the students.

Connecting course and survey content

The case-review format of the ECO survey was inspired by the student-active teaching methods highlighted in TIEE and similar resources. It is an excellent way to get students thinking critically about the applied context of ecological fundamentals. There are, of course, many real-world contexts for any given aspect of ecological dynamics. For example, in ecology and environmental science classes top-down / bottom-up forcing in community dynamics is often discussed in the context of wolf-moose-vegetation populations on Isle Royale (e.g. McLaren and Peterson 1994; c.f. Fortier 2002). Some of the same ecological principles considered in that case study are relevant in the context of predator reintroductions, such as gray wolf reintroduction in the United States (one of the survey issues). By connecting survey content to course topics, the ECO survey can be used to assess student learning or changes in student perspectives in relation to those specific course topics. Consequently, the impact or effectiveness of the teaching methods used to introduce or develop those areas of the course can be evaluated as well. In the survey administered at VMI, half the conflicts reviewed in the ECO survey corresponded to student-active classroom exercises in the course (Table 1). The stakeholder perspectives and conflicts were not discussed explicitly in class, but some ecological aspects of the issue were discussed. For example, the VMI course employed the TIEE figure set by Shusler (2004) on forest community impacts from high deer densities to review indirect connections in communities (e.g., deer impacts on breeding bird populations; McShea and Rappole 2000). We did not discuss the economic aspects of deer hunting or crop damage; however, these stakeholder issues were raised in the ECO survey. In this way, students needed to consider their ecological understanding of the issue in the new context of these stakeholder concerns. Standardizing teaching methods between courses at the two institutions was not feasible; therefore, we only examine connections between specific teaching methods and ECO survey responses from students at VMI.

| Issue | Level of Organization | Ecological Principles | Teaching Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Protected Areas | Populations, communities | Population dynamics and harvest management; food webs and trophic dynamics. | Lecture |

| Wolf Reintroduction | Predator-prey, community. | Role of top predators in community structure / stability; ecological uncertainty | Case study (Fortier 2002) and guided discussion. |

| Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) | Ecosystem | Connections in open systems; long-term impacts of human activity. | Lecture |

| Deer Population Management | Populations, communities | Community dynamics and succession, particularly as related to overabundance; population management. | Pairs share and guided discussion following TIEE article (Shusler 2004); guided discussion and citizen's argument following case study (Ribbens 2001) |

| Invasive Species | Populations, communities | Population dynamics and community impacts of invasive species; control of invasive species. | Informal group work and guided discussion following TIEE article (D'Avanzo and Musante 2004) and review article (Simberloff 2005) |

| Deforestation | Population, community | Forest succession; community / food web dynamics. | Lecture |

The post-course survey also contained three free-response questions asking students to briefly reflect on the course and what they learned. We were interested in querying students about topics they favored during the course, as well as any class activities that they felt contributed (or did not contribute) significantly to their learning the material. The questions were intentionally general, to avoid leading

students toward identifying particular aspects of the course or types of activities:

What topic(s) covered in class did you enjoy most?

Do you feel that any particular class topics or activities contributed to any change in your perspective on the preceding environmental issues?

What topic(s) or activities do you feel contributed the LEAST to your experience in this course?

These questions were designed to determine if student-active course components were particularly formative in a student’s course experience. We analyzed individual differences in scores on the NEP and ECO pre- and post-course surveys at VMI as a paired design, and differences in PC survey scores using group comparisons. The post-course survey also requested basic demographic data on each student. We do not present analyses of these data here, as sample sizes were too small for meaningful assessment of demographic biases.

Survey distribution

The surveys were distributed in the first and last week of semester-long courses at Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and Phoenix College (PC) in the spring semester of 2006. The VMI course is an upper division general survey of ecology offered as an elective for majors in Biology, while the PC course is a lower division survey of environmental biology for both science and non-science majors. Both courses introduce fundamental concepts of ecology including, but not limited to, population dynamics, trophic interactions and community dynamics. The institutions represent very different student demography and experience in biology. Comparisons between survey results from these schools provide a qualitative, first-order assessment of transferability of the survey between different student populations. Extensive steps were taken to ensure anonymity for the students At VMI a third party provided each survey with a numeric code replacing respondent identity so that pre- and post-course responses could be compared. Respondent identity was not coded at PC, therefore pre- and post-course comparisons were not possible with this sample. Completed surveys were withheld from the instructors until after the end of the semester, and the survey was not discussed in class except when instructing (and encouraging) students to respond honestly and candidly. It was emphasized to students that the survey was being used to evaluate the course and its content, not to scrutinize their particular perspectives on environmental issues. The survey and administration protocol was approved by the Human Subjects and Animal Use Committee at Virginia Military Institute.

Results

Scores on the NEP and ECO surveys at Virginia Military Institute (VMI)

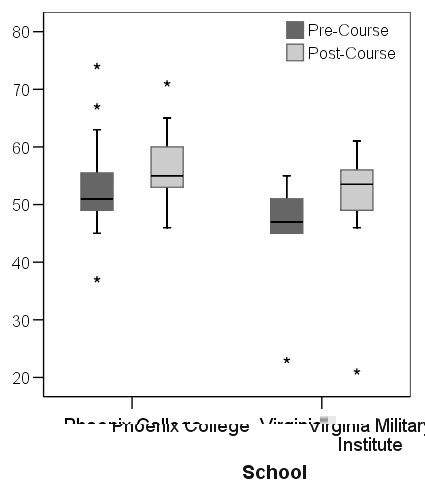

The survey was completed by 10 students at VMI and 31 students at PC. At VMI, scores on the pre-course NEP survey ranged from 23 to 55, with a mean of 45.9 and standard deviation of 8.7. Post-course scores ranged from 21 to 61, with a mean of 50.1 and standard deviation of 11.1. The apparent high variation in these scores is attributable to a single outlier point at the lower end of the scale (Fig. 1). Changes between pre- and post-course scores ranged from -3 to +14, with an overall average increase of 4.2 points (SD = 5.9). Pre- and post-course NEP score differences were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk statistic = 0.923, df = 10, p = 0.379), and therefore we used a paired t-test to assess significance. The differences were significant at α = 0.1 (t = -2.243, df = 9, p = 0.051), indicating a general shift toward decreasing anthropocentrism in environmental perspectives (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of pre- and post-course scores on the NEP survey at Phoenix College (N = 31) and Virginia Military Institute (N = 10). Modified boxplots indicate median, quartiles, total range, and potential outlier points (*). Increases in scores represent decreased anthropocentrism in student perspectives within institutions.

Changes in scores on the ECO survey identified changes in specific aspects of student perspectives at VMI. We scored individual surveys according to the five 'dimensions' of environmental attitudes identified earlier, and analyzed changes between pre- and post-course scores using pairwise t-tests. Results indicated that students reduced emphasis on economic priorities in their perspectives on issues (p < 0.001), demonstrated an increase in awareness of ecological principles underlying issues (p = 0.031), and showed decreased anthropocentrism in their perspectives (p = 0.027; Fig 2). Students did not appear to change their emphasis on stakeholder parity in resolving issues, nor did they demonstrate a significant change in environmentally conservative attitudes. Changes in student attitudes were relatively consistent across all issues; therefore, the teaching methods used when reviewing the ecology underlying these issues did not specifically effect attitude changes (Fig. 3).

Scores on the NEP and ECO surveys at Phoenix College (PC)

Surveys at PC were not individually coded and therefore paired comparisons were not possible. Pre-course NEP scores ranged from 37 to 74, with a mean of 52.4 and standard deviation of 7.2. Post-course NEP scores ranged from 46 to 71, with a mean and standard deviation of 56.5 and 5.7 respectively (Fig 1). Distribution of pre-test NEP scores was not normal (Shapiro-Wilk statistic = 0.912, df = 31, p = 0.015) so we compared distributions of pre- and post-test scores using Mann-Whitney tests. Post-test NEP scores were distributed differently from pre-test scores (U = 268, N = 31, p = 0.003) with an apparent shift toward higher scores on average (Fig. 1), likewise suggesting a shift toward increased ecocentrism (decreased anthropocentrism) among student attitudes.

The ECO survey at PC was modified and included only three of the six case reviews from the original survey. These responses did not provide enough data to assess significance; however, the general pattern of pre- and post-course changes qualitatively mirrored survey results from VMI (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Average percent change in scores within individual categories of student perspectives as suggested in ECO survey scores. Error bars show standard errors of mean change in a category across all ECO issues; in some cases these were not calculable for scores at Phoenix College. Symbols indicate significance of changes assessed in paired t-tests (* P<0.05; ** P<0.01).

Discussion

Our results indicate a general shift in environmental perspectives among students at both institutions with a corresponding increase in awareness of ecological principles. The change between pre- and post-course NEP scores suggests that students at both institutes demonstrated more ecocentric attitudes after completing their respective ecology and environmental biology courses. This is especially meaningful considering the differing demographics. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated increased concern for environmental issues among undergraduate students following a course in environmental science (Carpenter 1981; Leeming et al. 1993; Mangas and Martinez 1997; Zelezny 1999). The results of the ECO survey are in general agreement with NEP results, and they further indicate that certain aspects of student perspectives changed more than others.

Quantifying the constituent dimensions and structure of environmental attitudes is a complex area that is in need of further study (Heberlein 1981; Schultz et al. 2005). It is important to note here that the ECO survey has not been validated in application nor evaluated by experts in educational psychology; therefore, its results must be considered qualitative (Leeming et al. 1993). Much work remains to be done before it can be considered an accurate measure of environmental attitudes. However, general agreement in results from the NEP and ECO surveys lends qualitative credibility to its application as an indicator of changes in student perspectives when applied in a pre- and post-test format.

The largest change in student values indicated by scores on the ECO survey is in the emphasis placed on economic value of resources. Students appeared to reduce emphasis on economic gains from exploitation of natural resources in their perspectives on environmental conflicts. Certainly this reflects a decrease in anthropocentrism among students, and increased acknowledgement that those resources serve purposes other than exploitation; however, the structure of economic valuation is complex. Does this result reflect a shift in values (away from economic aspects), or a shift in the definition of a resource’s economic value? In other words, do students recognize an economic component to the ‘environmental service value’ of these resources that equals their exploitation (e.g. harvest) value, and therefore offset it? Does decreased emphasis on exploitation reveal an increased awareness of service value, or a greater emphasis on general conservation? This particular result indicates that this might be an interesting area to consider explicitly during a course, perhaps as a class discussion topic.

A goal of the ECO survey was to connect the topics to the course material and the teaching methods associated with that material. This was very challenging, due to the connections between ecological dynamics at different levels of organization. This may have contributed to the apparent lack of correlation between teaching methods and changes in attitudes or awareness (Fig 3). Patterns in free-response answers are difficult to characterize or generalize, however these queries did generate interesting feedback from the students. When asked what course topics they enjoyed most, 70% of students at VMI identified topics that were featured in student-active course exercises such as those adapted from TIEE articles (D’Avanzo and Musante 2004; Shusler 2004). Recall of course topics is biased by the survey content and connections to class topics, so the implications of this result are equivocal. However, it is worth noting that environmental conflicts in the survey were connected equally with topics that were taught using student activities and those covered only in lectures. Changes in student perspectives and understanding among individual ECO survey issue did not suggest a correlation with the teaching method employed for each topic (Fig. 3). However, this sample is likely too small to quantitatively address this with adequate precision.

Figure 3. Mean percent changes in scores within individual categories of student perspectives, separated by specific ECO survey topics (Virginia Military Institute only). JACADS refers to the chemical agent disposal facility at Johnson Atoll. Note that some categories were not assessed in all topics (e.g., Ecological Awareness was not assessed in the Deer Population Management issue). See Table 1 or supplemental material for more details on the specific aspects of student perspectives queried in each ECO section. Symbols indicate significance of changes indicated by pairwise t-tests († P < 0.1; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01).

The ability to connect the format and content of the ECO survey to activities and topics in an undergraduate ecology course makes it a useful tool for evaluating courses; however, it could also be applied as a course activity to provide context for ecological principles and generate discussion. In this study, we explicitly avoided discussion of the specific environmental issues summarized in the ECO survey to prevent bias in student responses. Our initial objective in this study was to develop a tool strictly for evaluating student attitudes; however, it is readily apparent that this survey could also function as a backdrop for in-class activities. If applied as a pre-course survey, the results could be raised in the context of course topics. Responses could be summarized and revealed to the class, whihc would stimulate discussion about the ecological aspects of environmental conflicts. Changes in student opinion could then be polled on the spot, or in follow-up writing assignments, which would give students the opportunity to reflect on how their new ecological knowledge may influence their perspective on the issues. The ECO survey does not require students to reflect on their own experiences, though the opportunity is there in the free-response questions; however, it is very difficult to characterize general patterns in these answers, and these questions likely function better as learning activities than as course evaluation tools. Utilizing the ECO survey as both a teaching tool and course evaluation instrument in the same course would constitute tautology, and therefore it should strictly be applied as one or the other. However, it offers a relatively straightforward application for generating student discussions in class and connecting ecological fundamentals to complex environmental issues.

Our results mirror previous studies that demonstrate the influence of undergraduate education in shaping environmental perspectives and values in students. Our results also suggest that the novel ECO survey has potential for use in evaluating student perceptions and course outcomes in undergraduate environmental biology or ecology classes. The survey requires further evaluation and validation before it can be considered a reliable measure of environmental attitudes (cf. Schindler 1995; 1999). Subsequent analyses will focus on evaluating the study in different student groups to determine its reliability and consistency. The New Ecological Paradigm (Dunlap et al. 2000) and other established surveys provide a more reliable scale of anthropocentrism in perspectives (Leeming et al. 1993). The ECO survey will benefit greatly from application and critical evaluation in a variety of courses and institution settings. We welcome and encourage faculty who wish to collaborate on further application of the ECO survey to contact us.

Practitioner Reflections

The ECO survey has potential as a means of assessing student perspectives and ecological understanding in a pre- and post-intervention context. It is presently imperfect as a tool for identifying the impact or role of student-active teaching methods in effecting such changes, but we believe its conceptual structure holds potential – particularly if properly validated. However, it seems a logical conclusion that any methods that improve student learning in ecology will have greater impact on students' environmental attitudes. It may be that such impacts can not be separated out within a single course, particularly if the benefits of student activities extend beyond the specific course topic for which they are employed. It may be that using these approaches increases overall student 'investment' in the course, with impacts for learning across all course activities.

As discussed above, focusing class discussions toward the intended learning outcomes can be challenging. It is easier when students have already been given the necessary background to focus on the ecological fundamentals of the issue rather than the sociological implications. Using guided discussion as a means of introducing new material or concepts can be very effective, as it provides an early context for ecological principles and familiar foundation from which to develop more complex ideas. However, it can be more challenging to keep the discussion on track in these cases and teachers must be prepared to take a more active role in guiding students toward the desired endpoint. At VMI, using paper discussions or case studies to introduce new topics has been abandoned altogether as a result of critically evaluating learning outcomes in this study. These methods are employed only after a sufficient knowledge base at the associated level of organization (individual, population, community, etc.) has been established and students can more easily make connections between discussion issues and topics and ecological principles. This may not be necessary in advanced courses as opposed to general survey courses.

Several students also commented that in-class discussions were sometimes allowed to drift off topic, and therefore were not as well connected to the lecture material as they could have been. This was an important revelation that highlights the challenges of managing student activities. Allowing student interests to dynamically direct the focus of discussions is often an effective way to engage more students in active debate. However, it can be difficult to redirect discussions that have become tangential to the ecological focus – particularly when the topic is emotionally evocative and class time is limited. As instructors, these comments spurred us to examine our own approaches to facilitating and moderating student discussions and activities. We realized that student engagement alone is not necessarily an indicator of productive discussion. Instructors need to be prepared to redirect discussion foci toward the teaching goals quickly, especially in a typical lecture period (50 minutes). Information to assist instructors on applying student active methods can be found in the Teaching section of TIEE (see Resources).

Even though our initial objective in this study was to develop a tool strictly for evaluating student attitudes, it became readily apparent that the ECO survey could also be used for in-class activities. This was tested at VMI recently with encouraging results; however, the caveat regarding the instructor's role in focusing discussion was very applicable here. The divisive nature of the ECO conflicts can lead to contentious debate that is often more political than environmental. This has some benefits, in that the political aspects of policy-making provide real-world context for challenges facing conservation. A discussion that is too emotionally charged can lead to negative returns, therefore establishing ground rules

for productive and considerate discussion was helpful. However, passionate involvement in environmental causes has produced important progress in the past. Perhaps it is not unhealthy to allow emotion to enter the room when students debate such things, but it is best for instructors to take a neutral stance. Independence of student thought underlies the strength of student-active teaching methods, and compromising that independence would likely compromise the learning benefits.

References

- Benton, R. 1993. Does an environmental course in the business school make a difference? Journal of Environmental Education 24:37-43.

- Carpenter, J.R. 1981. Measuring effectiveness of a college-level environmental earth-science course by changes in commitment to environmental issues. Journal of Geological Education 29:135-139.

- D'Avanzo, C. and S. Musante. January 2004, posting date. What are the impacts of introduced species? Teaching Issues and Experiments in Ecology, Vol. 1: Issues: Figure Set # 2 [online]. http://tiee.ecoed.net/vol/v1/figure_sets/species/species.html

- Diduck, A. 1999. Critical education in resource and environmental management: Learning and empowerment for a sustainable future. Journal of Environmental Management 57:85-97.

- Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. Mertig, A.,& R.E. Jones. 2000. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues 56:425-442.

- Fortier, G.M. 2002. The wolf, the moose, and the fir tree: who controls whom on Isle Royale? National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, University at Buffalo, State University of New York. (http://ublib.buffalo.edu/libraries/projects/cases/Isle.html)

- Heberlein, T.A. 1981. Environmental Attitudes. Zeitschrift fur Umweltpolitik (Journal of Environment Policy) 81(2):241-270.

- Leeming, F.C., W.O. Dwyer, B.E. Porter, and M.K. Cobern. 1993. Outcome research in environmental education: a critical review. Journal of Environmental Education 24(4):8-21.

- Mangas, V.J. and P. Martinez. 1997. Analysis of environmental concepts and attitudes among biology degree students. Journal of Environmental Education 29(1):28-34.

- McLaren, B.E. and R.O. Peterson. 1994. Wolves, moose, and tree rings on Isle Royale. Science 266(5190):1555-1558.

- McNeal, A.P. and C. D'Avanzo. 1997. Student-Active Science: Models of Innovation in College Science Teaching. Saunders College Publishing. Harcourt Brace & Company, Orlando, FL.

- McShea, W. J. and J. H. Rappole. 2000. Managing the abundance and diversity of breeding bird populations through manipulation of deer populations. Conservation Biology 14(4):1161-1170.

- National Research Council. 1999. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. National Academy Press. Washington, DC.

- National Research Council. 2000. Inquiry and the National Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning. National Academy Press. Washington, DC.

- Ribbens, E. 2001. Too many deer! A case study in managing urban deer herds. National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, University at Buffalo, State University of New York. Viewed 1 May 2007. (http://ublib.buffalo.edu/libraries/projects/cases/guidelines.html).

- Rickinson, M. 2001. Learners and learning in environmental education: a critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research 7(3):207-320.

- Schindler, F.H. 1995. The development and validation of an ecology issue attitude instrument for college students and the outcomes. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Iowa, Iowa City.

- Schindler, F.H. 1999. Development of the Survey of Environmental Issue Attitudes. Journal of Environmental Education 30(3):12-17.

- Schusler, T.M. August 2004, posting date. Ecological Impacts of High Deer Densities. Teaching Issues and Experiments in Ecology, Vol. 2: Issues: Figure Set #2 [online]. http://tiee.ecoed.net/vol/v2/issues/figure_sets/deer/abstract.html

- Schultz, W.P. Gouheiva, V.V, Cameron, L.D., Tankha, G., Schmuck, P., and F. Marek. 2005. Values and their relationship to the environmental concern and conservation behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 36(4):457-475.

- Simberloff, D. 2005. The politics of assessing risk for biological invasions: the USA as a case study. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20(5):216-222.

- Zelezny, L.C. 1999. Educational interventions that improve environmental behaviors: a meta-analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education 31(1):5-14.